From mudbrick mosques rising out of the Sahel to turquoise-tiled minarets in Central Asia, Islamic architecture is far more diverse than most people expect. Kuala Lumpur’s Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia brings these global traditions together under one roof.

The Great Mosque of Djenné in Mali rises out of the dirt like a mirage, yet feels like a surreal extension of the earth it has come from. It’s all made of adobe – in fact, it’s the largest mudbrick building in the world. And the three grand towers rising above the fortress-esque east wall are all laced with wooden poles, jutting out as if would-be invaders have been throwing lances at it.

The poles, essentially, act as scaffolding. Which comes in handy every year, when the local community gets together every year to refurbish the mosque. More soft mud is applied over the previous year’s wear and tear, and humidity-inflicted cracks are filled.

Contrasting styles in Islamic architecture

It looks, frankly, nothing like the Kalyan Mosque complex in Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Here, gigantic entrance portals are covered in dazzling glazed tiles and a turquoise dome fights for attention with a minaret that Genghis Khan allegedly thought so beautiful, he ordered it spared. Shaped a little like a pepper grinder, it is made of brick, but with such intricate patterning that at first glance the whole thing looks like a supersized carving.

Most people, it’s fair to say, are not going to gaze upon that minaret in real life. Uzbekistan, as with Mali, is not exactly a prime tourist destination. There’s a reason why these great pieces of Islamic architecture remain relatively obscure in comparison to the Taj Mahal or Alhambra. And this is where the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, one ot the top attractions in Kuala Lumpur, steps in.

Inside the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia

Kuala Lumpur’s most impressive museum is a sumptuous building in its own right, with the turquoise, calligraphy-lashed exterior dome meeting a glazed tile façade, fountain-centred courtyard and elegantly decorative inverted interior dome. Beautifully calligraphed Qu’ran manuscripts, silkwork, jewellery and ceremonial plates are on display from across the Islamic world.

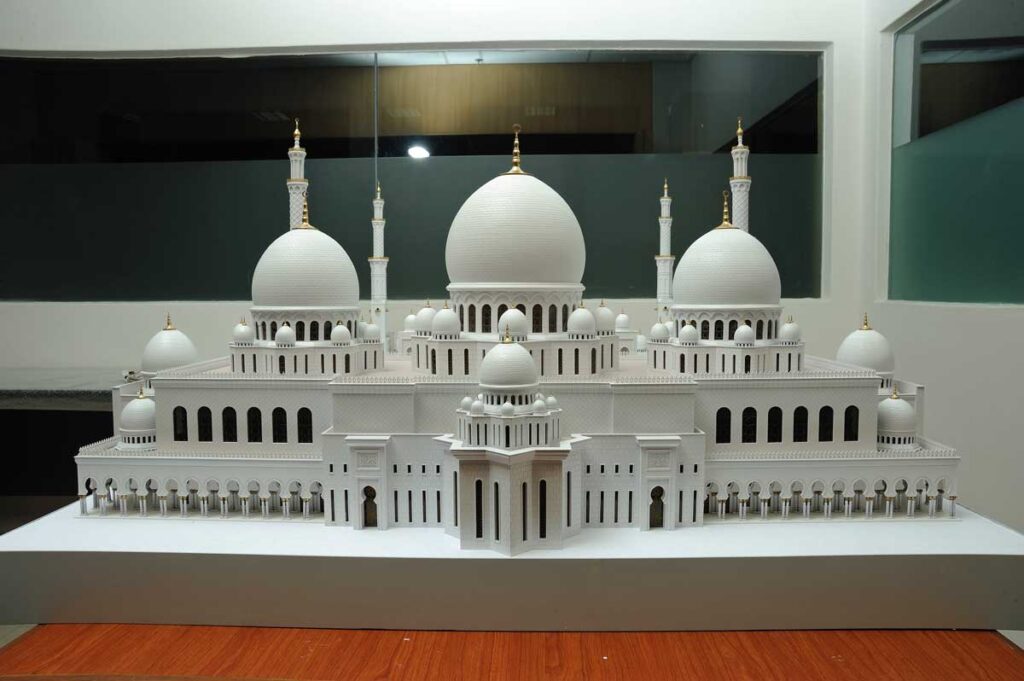

But it’s the Architecture Gallery that’s the biggest eye-opener – and an essential visit on a 48 hour Kuala Lumpur stopover. Over the 20 years the museum has been open, it has gathered together a collection of scale model mosques from all over the world. Some were commissioned locally, some put together by the Uzbek architectural firm that worked on the interior dome, and others have been gifts from embassies of foreign countries.

Why mosque architecture varies so widely

The overall idea is to allow people to get a look at buildings they might not ordinarily see – and for non-Muslims, those in Saudi Arabia in particular are essentially off-limits. But it’s also about giving an understanding of Islamic architecture – the main styles, features and underpinning core basics – plus the surprisingly large differences from one region to the next.

“It combats some taboos,” says Dr Heba Nayel Barakat, head of the curatorial department. “People think there’s just one style of mosque. There are some basic elements, but otherwise you can innovate and create some beautiful ideas more in keeping with local architectural trends.”

Early influences on Islamic architecture

Indeed, one that doesn’t really fit the classic template is the oldest-standing monument of Islamic architecture – the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. A shrine rather than a mosque, the octagonal building with an unmissable golden dome is where the prophet Mohammed’s ‘Night Journey’ – which culminated in his ascension to heaven – is believed to have started from.

From looking at it, it’s easy to see a heavy Byzantine influence. Dr Heba says that’s because nearby churches were used as an influence and – perhaps unexpectedly – those who built it weren’t Muslim. “They built on existing ideas, but these were regulated to suit the faith,” she explains.

Calligraphy, geometry and decoration in mosques

Primarily, this meant the removal of all human figures and images. Islam replaced pagan religions where idolatory was rife – and removing potential idols from religious buildings was major part of combatting this. This led to increased emphasis on three other elements – calligraphy, geometrics patterns and floral designs. The mosaics inside the Dome of the Rock, representing the gardens of paradise, are a classic example of the latter.

With time, styles changes, with new ideas coming during new caliphates and dynasties. The Great Ummayid Mosque in Damascus adapted the ruins of an existing church, turned a tower into a minaret, then built cloister-esque arched wings around a large central courtyard with a treasury building and fountain for ablutions.

Regional styles of Islamic architecture

The Abbasids moved the caliphate capital to Baghdad and built lavish, hypostyle mosques with columns and arches to forefront. Then in Persia and Central Asia, the biaxial four iwan style – four monumental entrances leading to separate halls from a central courtyard – became took hold. Glazed bricks and tiles were used to beautify and dazzle. And in Ottoman lands, prolific architect Sinan aped Istanbul’s Agia Sofia with huge, single confined spaces under a large dome – of which the bulging Selimiye Mosque in Edirne is chosen as the model example.

But the further away from the Arabian heartlands you get, the more unusual the models are. The wooden Masjid Kampung Laut in Kelantan, Malaysia was designed with local rainfall levels in mind. The three-tiered roof lessens the impact of the pouring rain, and the stilts keep it protected from floods. It’s also designed so that it can be moved if necessary.

Islamic architecture beyond the Middle East

Then the Great Mosque of Xi’an in China looks, to all intents and purposes, like a Chinese temple complex, with more than 20 buildings spread across a series of courtyards. Pavilions, painted beams, sculpted dragons and Chinese script all feature in the decoration. The main giveaways are a small golden crescent moon on the top of the prayer hall and the orientation – east to west to, ensuring the qibla faces Mecca, rather than feng shui-friendly north to south.

But probably the best illustration of Islamic architecture’s flexibility is the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. Originally built with palm tree logs and covered with reeds, it has been developed and vastly expanded time and time again, as a succession of rulers have put their mark on it and turned it into a behemoth. New ideas, it seems, have long been welcome.

Nearby attractions

- National Mosque of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur

- Perdana Botanical Gardens, Kuala Lumpur

- National Museum, Kuala Lumpur

- Central Market, Kuala Lumpur

- Petronas Towers, Kuala Lumpur

Frequently asked questions

What is the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia best known for?

It is best known for its extensive collections covering Islamic art and architecture, including scale models of mosques from around the world.

Does the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia cover global Islamic architecture?

Yes, the museum includes architectural models and artefacts from Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, China and Southeast Asia.

Why does Islamic architecture look so different from place to place?

While sharing core religious principles, mosque design adapts to local materials, climate, cultural traditions and historical influences.

Can non-Muslims visit the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia?

Yes, the museum is open to visitors of all backgrounds and provides context for understanding Islamic culture and design.

Is the Architecture Gallery a highlight of the museum?

Yes, it is often regarded as one of the most illuminating sections for understanding the diversity of Islamic architecture.