In north-east Pennsylvania, discover the origins of a multi-billion dollar industry that fuels the world.

The smell of Bradford, Pennsylvania

The sudden stench makes me start fretting. It’s not a natural smell – it’s a “there’s something wrong with the car” smell. Has something started leaking, or burning?

It’s late, it’s dark and I’ve just crossed the border from New York to Pennsylvania. I’ve been driving for four hours, and this wouldn’t be the greatest of places to break down.

I then notice the silhouette of the building to my right. It’s gargantuan, and just keeps on coming as I speed past. “Welcome to Bradford, Pennsylvania” says the sign. “Home of Brad Penn Motor Oil”.

The smell, it seems, is coming from the oldest continually operating lube oil refinery in the United States (their claim, and one that I cannot personally be bothered to factcheck). And that smell keeps on coming – the refinery is a hulking behemoth of place.

Where the oil industry began

It’s not perhaps what you’d expect to see here. Say “Pennsylvania” to me, and I instinctively conjure up images of farmland, forests and Amish buggies. Say “oil industry” meanwhile, and I’ll think offshore rigs, Saudi Arabia and Texas.

But it turns out that Big Oil kicked off in this north-eastern corner of Pennsylvania, with one of the world’s best industrial heritage sites in a little place called Titusville.

The birthplace of the oil industry is about an hour’s drive south-west from Bradford’s hulking refinery. It’s also a world away in looks. The world’s first oil well is surrounded by gentle, pretty forest. Leaves flutter down in their showy autumnal colours; walking trails slink into the woods, broadly following Oil Creek.

Oil Creek, Pennsylvania

As river names go, Oil Creek is not the sexiest. But it betrays what it used to be rather than what it is now. The modern day version is a tranquil affair, troubled only by the odd kayaker and over-enthusiastic dog let off its lead for a swim. In the 19th century, however, it was the major supply route for the black stuff as it was sent to refineries downstream.

In 1859, the main industry in these parts was lumber. But that was the year that Colonel Edwin Drake approached the Brewer, Watson and Company saw mill to ask if he could drill on their land. They agreed, and helped him out with repairing tools. On August 27th, he struck oil and the world changed.

Where Edwin Drake struck oil

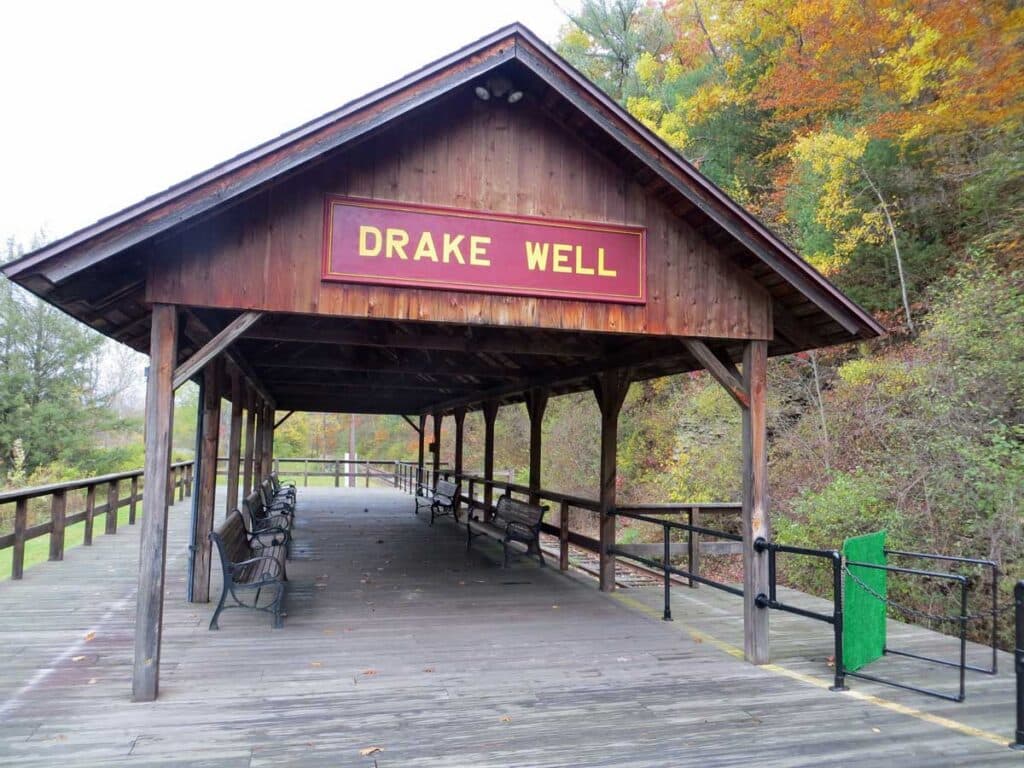

The exact site is marked with a plaque, and there’s now a museum next to Oil Creek.

I arrive on a Monday, when the Drake Well Museum is infuriatingly closed. Mercifully, however, most of the important stuff is outside. Old drilling machinery lies around on the grass, like some sort of rust-themed sculpture park. Each comes with a brief explanation of how it works, but the big steel derrick is the main attraction.

These things were designed to be portable, the clanking machinery cased in a slapdash home of wooden and corrugated iron. They’d be operated by a team of four – a roughneck, a roustabout, a driller and a tool dresser. It was sweaty, physical work.

Just how sweaty and physical is demonstrated by the earlier incarnation of the derrick. The spring pole rigs were a system of wooden beams and ropes. The technology dates back to before Christ – the Chinese used the principles to dig water wells.

Working the derrick

One has been set up for would-be oil barons to have a go on. You put your foot in a rope loop, lean forward and the rope works its way round a fulcrum to send an iron bit further into a hole in the ground. I have a pop, and hear the dull thud of the iron bit hitting the stone below. To dig through would require doing this thousands and thousands of times, each push making a barely perceptible impact.

And if you think oil prices are high now, just think how high they’d be if people still had to do this to get at it…

More Pennsylvania travel

Other Pennsylvania travel articles on Planet Whitley include:

- Understanding Abraham Lincoln in Gettysburg.

- Review of the very weird Mutter Museum in Philadelphia.

- Philadelphia‘s Eastern State Penitentiary – the prison that became a model for the world.

- Why you should visit the Benjamin Franklin Museum in Philadelphia.